Where is Southeast Asia?

The region we today know as Southeast Asia is recorded under many different names in maps from the past. The extent of territory that is depicted in these maps of the region also varies. These historical maps capture less a fixed geographical reality than the shifting assumptions about the region as a coherent and clearly delimited territory.

Explore SEAIf we look at the early maps of Southeast Asia we see it was called by many names. The historian Anthony Reid says the name Southeast Asia came into being in the Twentieth Century "an externally imposed geographical convenience [2]."

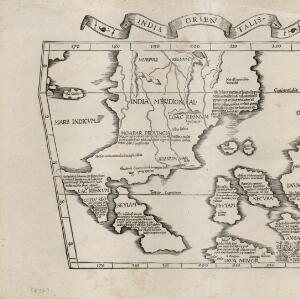

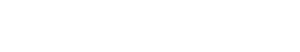

The names given to Southeast Asia often position it relative to the entity doing the naming, be that China’s "Nanyang" (Southern Ocean), Germany's "Hinter Indien" (Beyond India), or the Latin "Indiae Orientalis" (East Indies) of early modern maps [3].

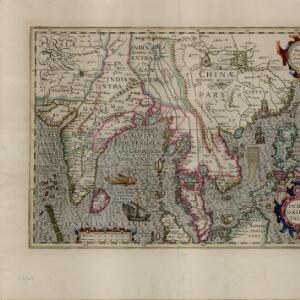

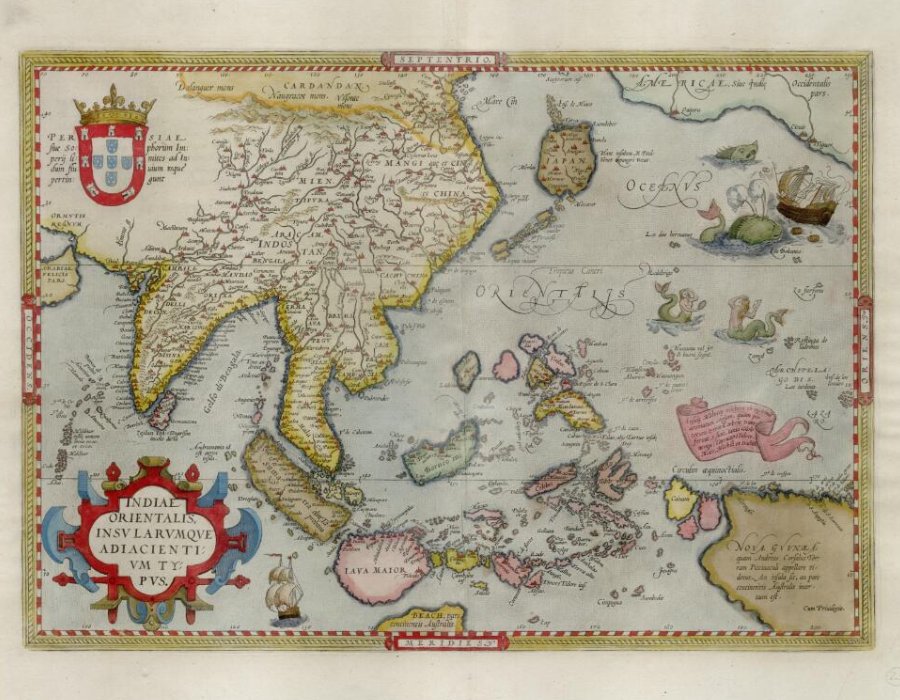

This 1570 map attributed to Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598), considered one of the founders of the Netherlandish School of Cartography, appears in an unidentified publication of the time. The map itself is titled East Indies and adjacent islands, but the publication places this map in a section about "Asia" and "Indonstan" and labels the image "India".

Indiae orientalis insvlarvmqve adiacientivm typvs

[East Indies islands and adjacent areas], 1570 [1].

The many India Orientalis

India Orientalis was the name used on maps depicting Southeast Asia in the early modern era of European map making. It is a Latin term meaning India of the east or as it came to be known, East Indies. What is included in maps of India Orientalis changes over time depending on the state of European knowledge and the perspective of the map maker. Sometimes peninsular Southeast Asia is present, sometimes not, and which islands are recorded, and by what name, varies. Explore the varied geographies of India Orientalis over time.

India Orientalis

[East Indies]. This early map of Asia includes text describing the local people, their religious beliefs, crops, spices etc. On the island labelled Angama there is a drawing of anthropophagi—members of a mythical race of cannibals—chopping up a human body [4].

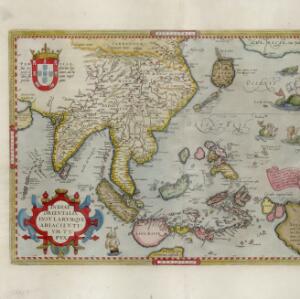

Indiae orientalis insvlarvmqve adiacientivm typvs

[East Indies and adjacent islands]. A red banner at the right features text that notes that the ‘Insule Molucce’ (Maluku Islands) are famous for their abundance of spices, which are sold across the world. There are also Illustrations of mermaids and sea monsters wrecking a ship [10].

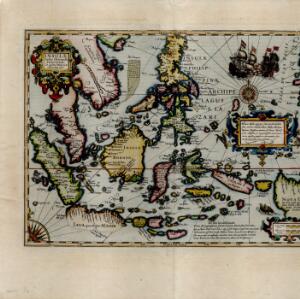

Insulæ Indiæ orientalis præcipuæ: in quibus Moluccæ celeberrimæ sunt

[Principal islands of the East Indies: in which the Moluccas are most renowned]. On the right of this map, Latin text held within an elaborate border notes that five of the Maluku Islands are located nearby—Ternate, Tidore, Moti, Makian and Bacan—which trade spices including clove, cinnamon, nutmeg and ginger to the world [11].

India Orientalis

[East Indies]. As was common in this era, this map mistakenly shows the bottom of Peninsula Malaya as a separate island. The map also features illustrations of ships and a sea monster. Text on the reverse describes the people, crops, geography of the region [12].

By the mid-17th century, maps were appearing that depicted Southeast Asia much as we know it today. A notable exception was New Guinea which—if it was featured at all—often had very vague coastlines, and was even shown attached to the Australian landmass.

India quae Orientalis dicitur, et insvlae adiacentes

[India which is called Eastern, and adjacent islands]. French text on the reverse of this map describes the religion, languages, crops, trade etc. of Aracam and Pegu (Myanmar), Siam (Thailand), Cambaja (Cambodia). The map is dedicated to the Dutch merchant Christophoro Thisio [13].

Nova tabvla India Orientalis

[New Map of the East Indies]. An early 18th century map of the Indian Ocean, illustrated with a drawing of Asian merchants riding an elephant and using a camel to transport their goods. Other men use bows and arrows to hunt ostriches. Ships are also shown sailing on the ocean [14].

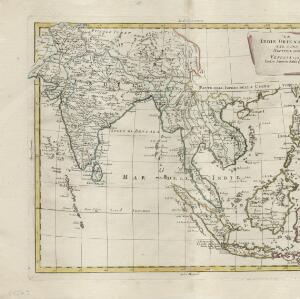

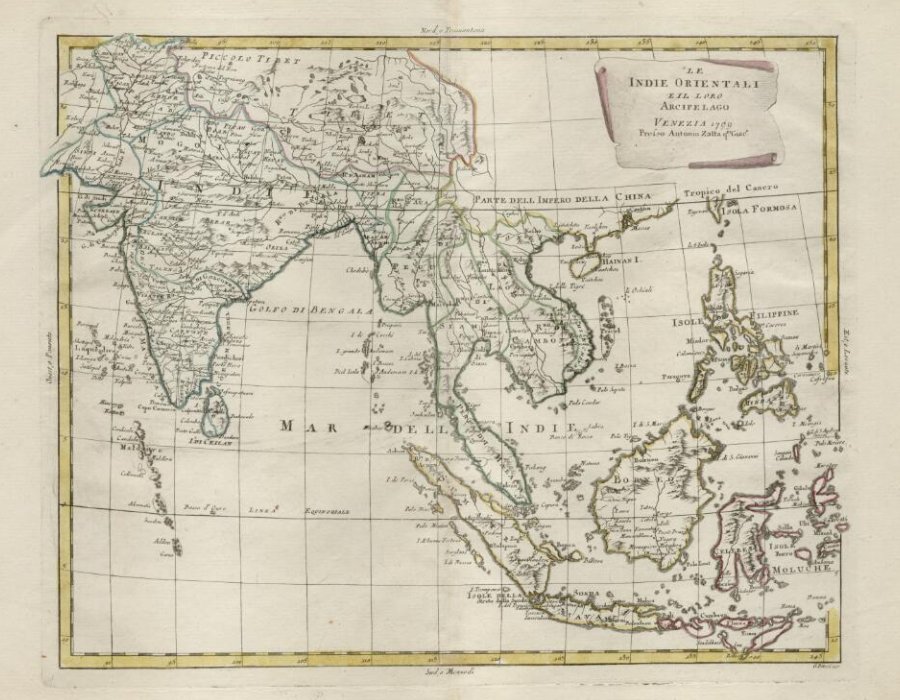

Le Indie Orientali e il loro archipelago

[The East Indies and its archipelago]. A late 18th century map of Asia featuring rivers, mountains, reefs and shoals. Regions are colour-coded, with the borders of the kingdoms of mainland Southeast Asia in green, and the islands of maritime Southeast Asia in yellow and red [15].

India Beyond the Ganges

In many early European maps of Asia the Ganges River served as a boundary marker, with Southeast Asia understood as the India or Indies “beyond” the Ganges [16].

1643

1740

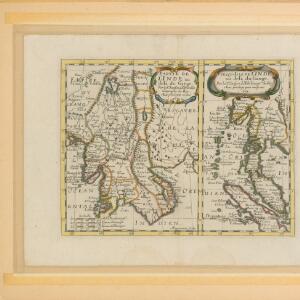

These two mid-17th century French maps are by the French cartographer Nicolas Sanson, referred to as the father of French cartography. The maps depict the part of India "delà du Gange", meaning beyond the Ganges (the map on the left), and the "presqu-Isle de L'Indie au delà du Gange", meaning the peninsular of the Indies beyond The Ganges (the map on the right).

Sinca pura [Singapore] is named, but not shown as an island separate from the Malay Peninsula. Penang is labelled as P.Pinaon, a named used by Manuel Godinho de Erédia (1563-1623), a Bugis-Portuguese documenter of the region. The important trading port of Malacca is shown.

Partie de l'Inde au delà du Gange / Presqu'isle de l'Inde au delà du Gange

[Part of India beyond the Ganges / Peninsula of India beyond the Ganges]. 1652 [17].

Whose

Southeast Asia?

During the period of European imperialism, the territories and islands of Southeast Asia were claimed as the being under the control of different European powers. The East Indies was carved up into French, Portuguese, Spanish and British territories, which changed over time. Explore the changing colonial geographies of Southeast Asia.

Hinter Indien nebst den Hinterindischen Inseln

[Further India and the Further Indian Islands]. 1836 [18].

This 1836 map by the German map maker Karl Ferdinand Weiland (1782–1847) refers to Southeast Asia as "Hinter Indien" (Further India) and the Hinterindischen Inseln (Further Indian Islands). Coloured borders identify the colonial possessions of Britain, the Netherlands, Spain, Denmark and Portugal at the time in Southeast Asia.

These "frontier" lines were to avoid disputes between European colonists, who were all competing to trade resources from Asia. They did not mark national boundaries as we know them today.

The political map of Southeast Asia was redrawn many times. As the historian Nicholas Tarling notes, this redrawing "was not complete—even on the map, let alone on the ground—till the early twentieth century [19]."

This Dutch map shows the border (in orange) agreed between British and Dutch territory on Borneo in 1891. Alternative claims are also shown on the eastern reaches of the border: according to the Dutch (blue), the British (green), and the British North Borneo Society (yellow) [20].

Coloured colonial territorial lines marked on a map implied a certainty of authority that did not always exist.

They did not always reflect on-the-ground economic, social, cultural, ethnic or even geographical realities.

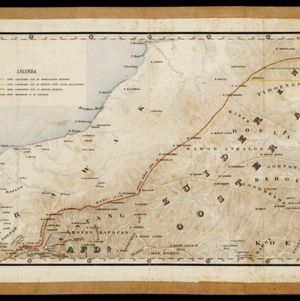

Sometimes that on-the-ground reality included organised resistance to colonial authorities. For example, between 1873 and 1904 the Acehnese actively resisted Dutch presence in Sumatra. This Dutch map of the Aceh War records the changing areas in which the Dutch acted between 1873 and 1896.

Historische, chronologische overzichtskaart van den Atjeh oorlog

[Historical, chronological overview map of the Atjeh war]. 1898 [21].

Explore More

Reference

[1]

Ortelius, Abraham. Indiae orientalis insvlarvmqve adiacientivm typvs. 1570. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26056099D> (accessed August 24, 2022).

[2]

Reid, Anthony, "Introduction: A time and a place." In Reid, Anthony, ed. Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Era: Trade, Power, and Belief, pp. 1-19. Cornell University Press, 1993.

[3]

Emmerson, Donald K. "'Southeast Asia': what's in a name?" Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 15, no. 1 (1984): 1-21. See also Solheim, Wilhelm G. "'Southeast Asia': What's in a Name", Another Point of View." Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 16, no. 1 (1985): 141-147. The debates about what and where Southeast Asia is has been linked to the fact that it lacks "geographical obviousness," made up as it is of discontinuous territories and islands. See Van Schendel, Willem. "Geographies of knowing, geographies of ignorance: jumping scale in Southeast Asia." In Kratoska, Paul H., Remco Raben, and Henk Schulte Nordholt, eds. Locating Southeast Asia, pp. 275-307. Brill, 2005.

[4]

Wheatley, Paul. "Lochac Revisited." Oriens Extremus 16, no. 1 (1969): Pages 85-110. Fries, Lorenz (following Ptolemy). India Orientalis. 1535. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26055960K> (accessed August 24, 2022).

[5]

Suarez, Thomas. Early mapping of Southeast Asia: the epic story of seafarers, adventurers, and cartographers who first mapped the regions between China and India. Tuttle Publishing, 2012.

[6]

Marco Polo, quoted in Suarez, Thomas. Early mapping of Southeast Asia: the epic story of seafarers, adventurers, and cartographers who first mapped the regions between China and India. Tuttle Publishing, 2012. Page 297.

[7]

Van Duzer, Chet. Henricus Martellus’s World Map at Yale (c. 1491): Multispectral Imaging, Sources, and Influence. Springer, 2018. Page 75.

[8]

Van Duzer, Chet. Op cit. Page 102.

[9]

Van Duzer, Chet. Martin Waldseemüller's 'Carta marina' of 1516: Study and Transcription of the Long Legends. Springer Nature, 2020. Footnote 359.

[10]

Ortelius, Abraham. Indiae orientalis insvlarvmqve adiacientivm typvs. 1579. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26055948F> (accessed August 24, 2022).

[11]

Mercator, Gerhard, and Hendrik Hondius. Insulæ Indiæ orientalis præcipuæ: in quibus Moluccæ celeberrimæ sunt. 1606. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26055925A> (accessed August 24, 2022).

[12]

Hondius, Jodocus. India Orientalis. 1636. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26055970A> (accessed August 24, 2022).

[13]

Jansson, Jan, Hendrik Hondius, and Christophoro Thisio. India quae Orientalis dicitur, et insvlae adiacentes. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26055978I> (accessed August 24, 2022).

[14]

Allard, Carel. Nova tabvla India Orientalis. c.1702-1705. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26055990C> (accessed August 24, 2022).

[15]

Pitteri, Giovanni Marco. Le Indie Orientali e il loro archipelago. 1799. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26055989K> (accessed August 24, 2022).

[16]

Boisseau, Jean. Indes orientalles ou du Gange. 1643. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-B26056105C> (accessed August 24, 2022).

Bowen, Emanuel. A new and accurate map of the Empire of the Great Mogul, together with India on both sides of the Ganges, and the adjacent countries. c.1740. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/bodleian-0310> (accessed August 24, 2022).

[17]

Sanson, Nicolas, and A. Peyounin. Partie de l'Inde au delà du Gange / Presqu'isle de l'Inde au delà du Gange. 1652. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/nlb-050000161> (accessed August 24, 2022).

[18]

Weiland, Karl Ferdinand. Hinter Indien nebst den Hinterindischen Inseln. 1836. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/leiden-876351> (accessed August 24, 2022).

[19]

Tarling, Nicholas. The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Volume 2. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

[20]

Kaart van een gedeelte van Borneo: met aanwijzing van de grens tusschen het Nederlandsch gebied en dat van het Britsche Protectoraat. 1891. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/leiden-1997072> (accessed August 24, 2022).

[21]

Historische, chronologische overzichtskaart van den Atjeh oorlog. 1898. "Digital Historical Maps Of Southeast Asia". <https://historicalmaps.yale-nus.edu.sg/catalog/leiden-2011284> (accessed August 24, 2022).